Practicing YAGNI

Main Thread Talks • 4 min read

Last week I spoke at Laracon US 2016 about Practicing YAGNI. First, let me say it was an honor to present for such a large audience at such a premiere conference. I received a lot of feedback and interest in my talk.

To that point, many people have asked me to share my slides. As the slides were mostly placeholders for discussion, I felt a blog post would better summarize the talk. However, if you must see those slides, you can watch my talk, and other Laracon talks, on StreamACon.

I consider myself a searcher. On a quest to find the Holy Grail of programming practices - that single practice which instantly levels up my skills. While I know this doesn't exist, I do believe in a set of practices. Recently, I found one to be YAGNI.

YAGNI is a principle of eXtreme Programming - something I practice daily at work. YAGNI is an acronym for You Aren't Gonna Need It. It states a programmer should not add functionality until deemed necessary. In theory, this seems straightforward, but few programmers practice it.

Why practicing YAGNI is hard

Before we continue talking about YAGNI, we need to understand the problem it solves. The problem is over engineering. At some point, we started priding ourselves on complexity - obsessed with playing design pattern bingo and building ever more intricate architectures in our head.

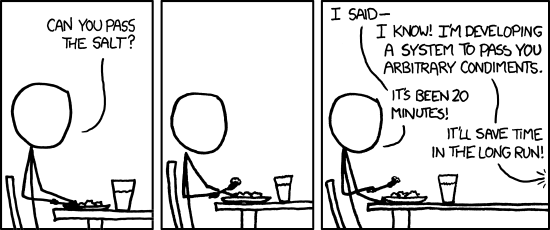

XKCD illustrates over engineering well with "The General Problem".

This is funny because it's true. But it begs the question - why can't we just pass the salt?

What ever happened to KISS? What's wrong with an MVP? The answer is nothing. We need to find our way back to simple. YAGNI can help us get there.

How to practice YAGNI

I think Ron Jeffries, one of the co-founders of eXtreme Programming, summarizes practicing YAGNI well:

Implement things when you actually need them, never when you just foresee that you need them.

Nonetheless, the most common contention is timing. We continually write code sooner than we actually need them. This is the over-engineer in us. We confuse foreseeing with needing.

To help distinguish between the two, we can create a time horizon. Kent Beck describes this well during an interview on Full Stack Radio:

…I did a little experiment… what if I deliberately stopped trying to predict the future and limit my design horizon to six months… things went better for me… I was less over engineering. I was making progress sooner. I was less anxious… Things were cleaner, easier to understand… So what about three months? One month? I never reached a limit with that experiment…

In this way, practicing YAGNI becomes a time experiment. One where we keep decreasing our time horizon to help limit the code we write. Ideally until we reach a point where we don't write code until it's actually needed. Not just because we're thinking about it, or want to, or it relates to code we're working on. We wait until the current code requires us to implement new code in order to work.

At first, I'll admit, this will feel like laziness. It's going to seem like you're intentionally avoiding writing code. In a way, this is true. The catch is, the code you're wanting to write isn't ready to be written. By waiting, you prevent all the bad things that happen when you make assumptions.

When not to practice YAGNI

Once you realize the benefits of YAGNI, you're going to try to apply it to everything (another programmer curse). You need to remember with great power, comes great responsibility. YAGNI isn't about saying no. YAGNI is about deferring unnecessary complexity.

As such, there will be times when you should not call YAGNI. Unfortunately, this takes experience. So I will outline a few scenarios to help those getting started.

- Learning something new: You should take the time when evaluating a new technology. You'll gain the time back later, and mitigate the risk of losing more time by making the wrong decision.

- Current design decisions based on future needs: YAGNI shouldn't handicap or sabotage our efforts. In these scenarios, make the future-proof design decision, but only implement enough to fulfill the current need. This allows us to limit rework, without completely undermining YAGNI.

- Abstracting external dependencies: External dependencies add complexity to your project. Inline with the previous examples, taking the time to abstract these dependencies will avoid rework and decrease the complexity.

- Testing, Security, Scale, and Business Requirements: Sorry, but YAGNI is not a free-pass on writing tests, secure code, considering scale, or business requirements.

What YAGNI means to me

Practicing YAGNI gives me confidence. I am comfortable delaying design decisions because I will be better informed in the future. I trust my ability to pivot quickly because my code is simple, making it easy to refactor and evolve. I write less code, and let's be honest, the best code is no code.

Find this interesting? Let's continue the conversation on Twitter.